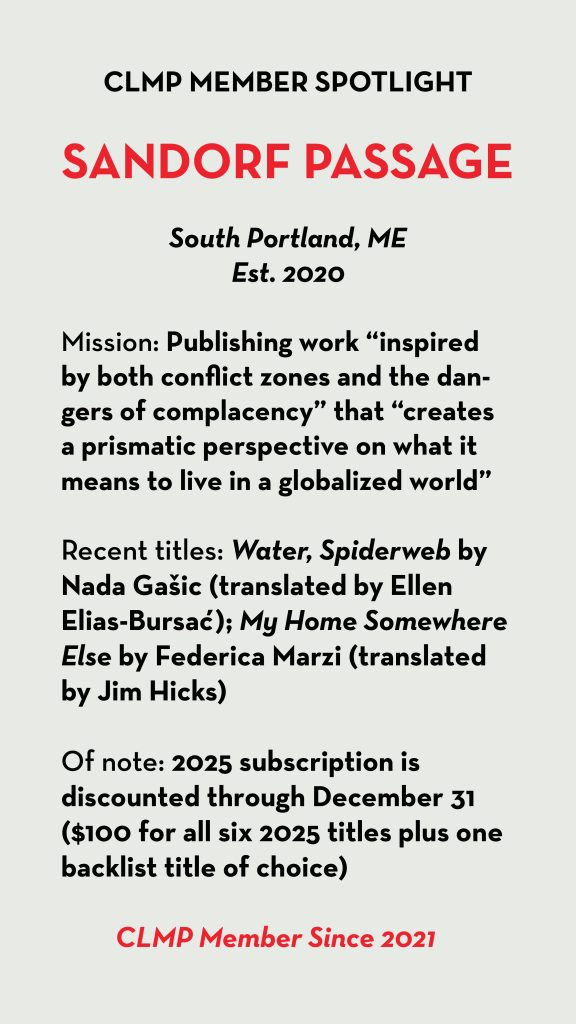

We spoke with Buzz Poole, cofounder and publisher of Sandorf Passage, in our latest Member Spotlight.

What is the history behind Sandorf Passage? When was it founded?

What is the history behind Sandorf Passage? When was it founded?

A chance meeting at the Frankfurt Book Fair sixteen years ago set me and Ivan Sršen on the path toward Sandorf Passage. A few years after that, Ivan introduced me to Croatian author Robert Perišić, giving Ivan and me our first chance to collaborate professionally. At the time, I was the managing director of Black Balloon Publishing, now an imprint of Catapult. I will forever be proud of being heavily involved with Robert breaking into English, first by acquiring Our Man in Iraq (Catapult, 2013), followed by my early editorial work on the No-Signal Area manuscript (Seven Stories Press, 2020), and then the two books of his that Sandorf Passage has published in translation so far: the story collection Horror and Huge Expenses (2021), which is how Robert became known in Croatia, and his latest novel,

A Cat at the End of the World (2022), a book I consider a true masterwork.

After Ivan and I worked together on some other publishing-related projects, in 2017, during the ALTA conference in Minneapolis, Ivan planted the seed of expanding his Zagreb-based publishing company, Sandorf. As we kicked around the idea over the next couple of years, we decided it would be best to establish a stand-alone entity in the States, and I incorporated Sandorf Passage as a nonprofit in Maine.

We squared away all the paperwork as 2020 was winding down, and we launched our first title, Bosnian author Vesna Maric’s The President Shop, in March 2021. It’s been a wild few years, but all things considered, I couldn’t be happier with our books and the growth we’ve experienced.

Part of your mission is to be “a home to writing inspired by both conflict zones and the dangers of complacency.” What does this mean to you, and why is it important?

So much of the trouble in the world today is the direct result of conflict zones, and conflict zones often emerge from cultural and political complacency. The stories we seek out and want to champion are responding to, or calling attention to, these dangers.

The first part of our mission is about publishing books that create “a prismatic perspective on what it means to live in a globalized world,” which is also an essential part of understanding what we do. For so long, there was a sentiment in American publishing that American readers didn’t want to read translated books other than the canonical classics. But today, we all live with the world in our pocket or on our desk. How we think about borders and boundaries has fundamentally changed, and giving Anglophone readers the chance to read stories they might otherwise never know about is more important than ever because they remind us that, for as different as aspects of life can be on the surface, the core elements of being human are the same all over the world. It’s vital to be presented with ideas that are “foreign” or “other” because that’s when you can gain new perspectives. And the books we publish from places beyond the former Yugoslavia also support the mission by showing additional new perspectives on what it means to live in a globalized world.

Why does Sandorf Passage focus on Balkan literature in particular? What can Balkan literature help us understand about our current moment?

Why does Sandorf Passage focus on Balkan literature in particular? What can Balkan literature help us understand about our current moment?

The obvious reasons for our focus are the relationship between me and Ivan and the fact that we were able to start this endeavor with EU funding that is specifically designated to bring books by authors from the former Yugoslavia into English.

What so impressed me when I read Our Man in Iraq was how someone of my generation wrote about the experience of living through war. As an American in his late forties, I’m no stranger to the idea of war, but it’s always been something that happens “over there,” not in our backyard. But here was this writer, more or less the same age as me, who literally lived through war in his backyard.

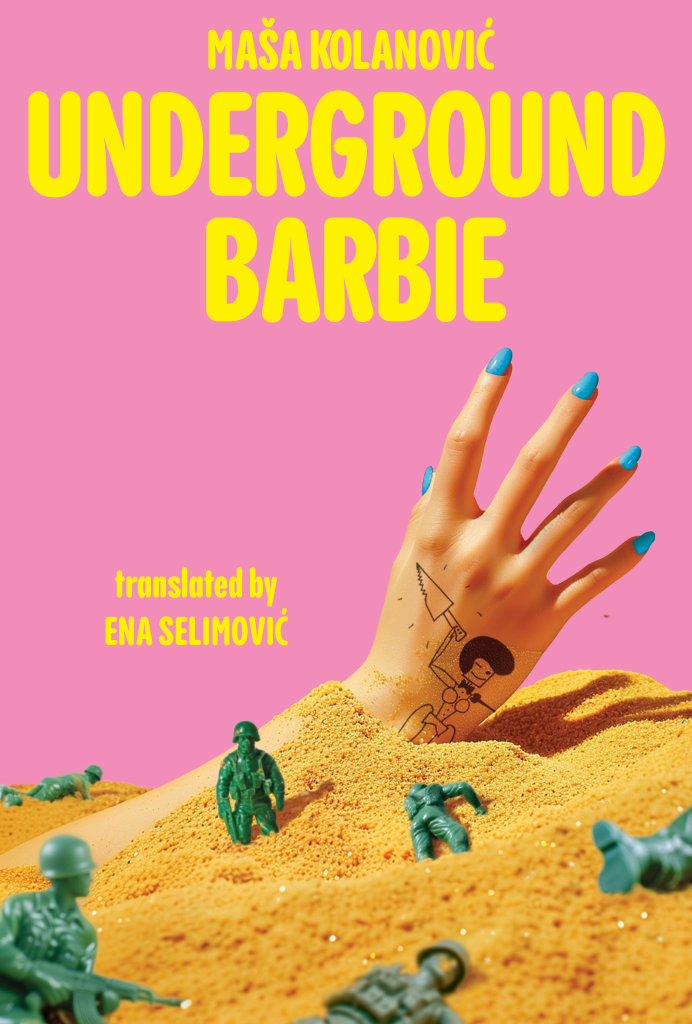

No one should have to experience this, but today there are far too many people suffering because of the military conflicts that are forced on them. Our January 2025 title is Maša Kolanović’s Underground Barbie (translated from the Croatian by Ena Selimović), which is about kids in an apartment block in Zagreb in the 1990s using their imaginations to cope and live through the ever-present specter of war. Looking at the state of the world today, the book is all too resonant, for me at least, in a way that, say, a French or German book about World War II isn’t, because Kolanović references things like Twin Peaks, things that are familiar to us as American readers, but are somewhat surprising in the context of Underground Barbie.

What are some of the rewards and challenges of publishing literature in translation?

Discovery is the greatest reward.

And while I know there are still some readers out there, and even some bookstore buyers, thinking they don’t want to read or stock translated books, in my mind, that’s more of their problem than Sandorf Passage’s. The real challenges are the ones that plague all independent publishers, especially small ones with limited financial means. How do we make our books known in a media landscape that is little more than chaotic noise? How do we find our readers, and our champions in the bookstores, and maintain those relationships? How do we deal with the rising costs of paper and shipping? Elements of these answers change title to title, which is part of the fun. But the unfortunate reality when it comes to addressing other parts of these questions is that money is the answer, and in some ways money is the only thing anyone is paying attention to. It isn’t a coincidence when a book is reviewed by every high-profile outlet and the author is the subject of multiple features and said book is stacked high in both chains and indies and the algorithms push it through wherever we go online—this is simply the result of robust PR and marketing budgets being put to use. And to be clear, some books that enjoy this success are tremendous. But think what could be possible if more space was made for books that are just as good, if not better, than the preordained critical darlings and bestsellers.

Can you tell us about some of your recent or forthcoming titles?

Can you tell us about some of your recent or forthcoming titles?

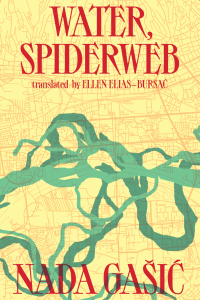

In October, we released the Croatian novel Water, Spiderweb by Nada Gašic (translated by Ellen Elias-Bursać), a noir-ish, multigenerational love letter to Zagreb. And in November, we published Federica Marzi’s My Home Somewhere Else (translated from the Italian by Jim Hicks), which really captures what it means to be an immigrant as seen through ideas about language and translation.

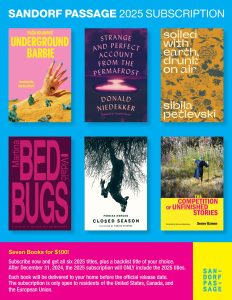

And I am absolutely thrilled about next year: Underground Barbie, which the Guardian hailed as “remarkable”; Martina Vidaić’s Bedbugs (translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursać), winner of the 2023 European Union Prize for Literature; Strange and Perfect Account from the Permafrost by Donald Niedekker (translated by Jonathan Reeder), a Dutch novel about a 16th-century polar explorer who speaks across centuries from his icy grave—a highly inventive and delightfully subtle climate change novel; Sener Ozmen’s The Competition of Unfinished Stories (translated by Nicholas

Glastonbury), a bawdy and hilarious Kurdish novel about an atheist who teaches at a religious school in occupied Kurdistan; Sibila Petlevski’s poetry collection, Soiled With Earth, Drunk on Air, self-translated from the Croatian; Monika Herceg’s latest award-winning poetry collection, Closed Season (translated from the Croatian by Marina Veverec), which Olga Tokarczuk lauds: “These are words like ‘quantum,’ ‘atom,’ ‘cosmos,’ ‘Hera,’ ‘Athena,’ that is, concepts that have roots elsewhere . . . I did not expect her poetic imagination to go in such a direction. It’s the imagination of someone free.”

What other initiatives or projects are you looking forward to in 2025?

I am very excited about offering our first subscription program for the 2025 list. It is currently live on our site and anyone who subscribes before the end of the year will get seven books for $100; this includes our six 2025 titles and a backlist title of their choice. Folks can subscribe next year, but they will only get the six new books. And moving forward, we’re thinking about how to enhance subscriber perks. Perhaps there will be subscriber exclusives—like online reading groups, signed copies, merch. Time will tell.

And because we have all the books lined up for next year, we’re printing more ARCs than ever before, with the aim of getting more bookstores to get their customers excited about what we do.

What are some other presses, literary journals, and organizations you admire that also publish “work that creates a prismatic perspective on what it means to live in a globalized world”?

It’s no secret that there are publishers, many of them CLMP members, that, like us, focus on work in translation, and I read books from all of those publishers. I am particularly fond of projects that take me, as a reader, somewhere unexpected. With so much of my reading and thinking dominated by Sandorf Passage, when I read for pleasure, I don’t search for a specific publisher. I look for something different from everything else I’ve been reading.

But, if I have to name names, I’ll float one outside the usual suspects: Versopolis. This pan-European project for helping poets transcend national boundaries has been around since 2014 and continues to grow, through publications, podcasts, and festivals. It’s a great resource for discovering contemporary international voices.