We spoke with Adam Z. Levy and Ashley Nelson Levy, the cofounders and publishers of Transit Books, in this installment of the CLMP Member Spotlight series.

What is the history behind Transit Books? When was it founded and what was the original mission?

Adam: We founded the press in 2015 to publish books by international and American writers that carry readers across borders and communities. That means prioritizing works in translation, works by international writers, works that push formal boundaries, works that have the capacity to challenge and excite—works, generally speaking, that we consider underserved by commercial publishing. And we wanted to bring them out in a way that celebrated their particularity and their difference while elbowing our way into the market to give these books and authors mainstream attention. Transit Books has stayed true to that founding mission, and we’re humbled by the success we’ve been able to achieve along the way.

Adam: We founded the press in 2015 to publish books by international and American writers that carry readers across borders and communities. That means prioritizing works in translation, works by international writers, works that push formal boundaries, works that have the capacity to challenge and excite—works, generally speaking, that we consider underserved by commercial publishing. And we wanted to bring them out in a way that celebrated their particularity and their difference while elbowing our way into the market to give these books and authors mainstream attention. Transit Books has stayed true to that founding mission, and we’re humbled by the success we’ve been able to achieve along the way.

Ashley: While this mission steers the little ship of our Transit logo, having a strong and consistent aesthetic was also important to us from the beginning—both through visual book designs and through the type of work we publish. We wanted readers to be able to pick up one of our titles and know immediately it’s a Transit book. There’s a wild range of styles within our catalog, but I think we’ve still managed to achieve that consistency, and I’m proud of this. And we’re always thinking about ways we can continue to push those boundaries.

Ashley: While this mission steers the little ship of our Transit logo, having a strong and consistent aesthetic was also important to us from the beginning—both through visual book designs and through the type of work we publish. We wanted readers to be able to pick up one of our titles and know immediately it’s a Transit book. There’s a wild range of styles within our catalog, but I think we’ve still managed to achieve that consistency, and I’m proud of this. And we’re always thinking about ways we can continue to push those boundaries.

In an interview with Guernica, you spoke about wanting to build a press on the principles of celebrating translation and translators, rather than hiding or downplaying “the fact that what you’re reading was not originally written in English.” What inspired this mission, and what are some of the ways you’re upholding it?

Adam: In the publishing industry, translation and translators have a history of being erased. The conventional wisdom has always been that translated literature doesn’t sell, and that if you’re reading something in translation, you might have to look to the title page to know it. Like many publishers now, we put the name of the translator on the cover. But that speaks to a very literal aspect of visibility, and I think advocating for the visibility of the translator and the translation is also about complicating our understanding of authorship. Many readers come to a text expecting to have a pure or at least a direct encounter with it, by which I mean an expectation that the book isn’t mediated by another person who is writing the text again in another language. Making translation more visible, then, means pulling back the veil on the translation process itself and being transparent with the reader about the choices a translator makes. Sometimes that means including a translator’s note in the book or online or featuring the translator in an interview or at an event, which we always try to do.

What are some of the benefits—and challenges—of being a small, non-profit press?

Adam: As a nonprofit publishing house, we’re guided by our mission and less so by the market, which enables us to take risks on the books we’re most excited about. And as a small publisher, we’re involved in a very hands-on way with our authors and translators throughout the publishing process, whether it’s thinking through an idea for a new project or going through edits or accompanying them on a tour.

Adam: As a nonprofit publishing house, we’re guided by our mission and less so by the market, which enables us to take risks on the books we’re most excited about. And as a small publisher, we’re involved in a very hands-on way with our authors and translators throughout the publishing process, whether it’s thinking through an idea for a new project or going through edits or accompanying them on a tour.

But of course there are a lot of challenges to running a small publishing house, especially a relatively young one—for instance, gaining a foothold in the market and being sustainable once having done so. But time and money are the biggest challenges. Ashley and I have both held full-time jobs elsewhere for much of the time since founding the press, and the press wouldn’t have been able to get off the ground without this.

Ashley: I second Adam’s comments here, especially those about time and money. A benefit I would add is working with Adam. When the two of us get going on a book together, the world gets all charged up and we remember why we started this thing in the first place.

September marks the publication of the first installments of the Undelivered Lectures series. Can you tell us a little about this series?

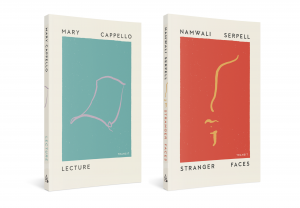

Adam: Yes! Undelivered Lectures is a long time in the making. We wanted to start a narrative nonfiction series to live alongside our Transit list that would provide an outlet for a certain kind of discursive prose. The book-length essays in this series have exceptional literary and cultural value, with writers contributing on a wide range of topics that show off what’s possible within the form. We’re excited to launch Undelivered Lectures with books on the lecture by Mary Cappello (Lecture) and on the contemporary mythology of the face by Namwali Serpell (Stranger Faces).

Adam: Yes! Undelivered Lectures is a long time in the making. We wanted to start a narrative nonfiction series to live alongside our Transit list that would provide an outlet for a certain kind of discursive prose. The book-length essays in this series have exceptional literary and cultural value, with writers contributing on a wide range of topics that show off what’s possible within the form. We’re excited to launch Undelivered Lectures with books on the lecture by Mary Cappello (Lecture) and on the contemporary mythology of the face by Namwali Serpell (Stranger Faces).

How has your own work as writers and translators influenced your roles as editors and publishers?

Ashley: My first book is coming out next year, and it’s been really interesting to see the process from both sides. I think a writer’s ear for language has steered me as an editor, and acquiring for the press has made me a better writer. We publish a small, highly curated list, and every book we put out must be special, without exception. I try to hold my own work to the standards of the press. And in that way, I’m always reading greedily and selfishly, to feed both hungry engines. There are so many tote bags about how joyous it is to read, but I would love to see a tote bag that says that reading is hard work. Some days I wish I could read like non-writers, non-editors, non-publishers do, with wholesome pleasure. But then something special comes across our desk and the thrill kicks in and all the hard work is done with its own kind of pleasure.