As part of our mission to support, celebrate, and promote literary magazines and presses, we showcase in this series short essays about the many publishers that have contributed to the collective story of independent publishing in our country.

In My Thirty Years’ War, the first volume of her three-part autobiography, Margaret Anderson wrote about the day she rented The Little Review’s office in Chicago’s Fine Arts Building: “I went into 917 the moment we signed the lease and spent the first day there alone, staring at the blue walls and living the future of The Little Review. I must say I foresaw it accurately—with the possible exception of my criminal record in the United States Courts for publishing the masterpiece of our generation—Ulysses.”

In My Thirty Years’ War, the first volume of her three-part autobiography, Margaret Anderson wrote about the day she rented The Little Review’s office in Chicago’s Fine Arts Building: “I went into 917 the moment we signed the lease and spent the first day there alone, staring at the blue walls and living the future of The Little Review. I must say I foresaw it accurately—with the possible exception of my criminal record in the United States Courts for publishing the masterpiece of our generation—Ulysses.”

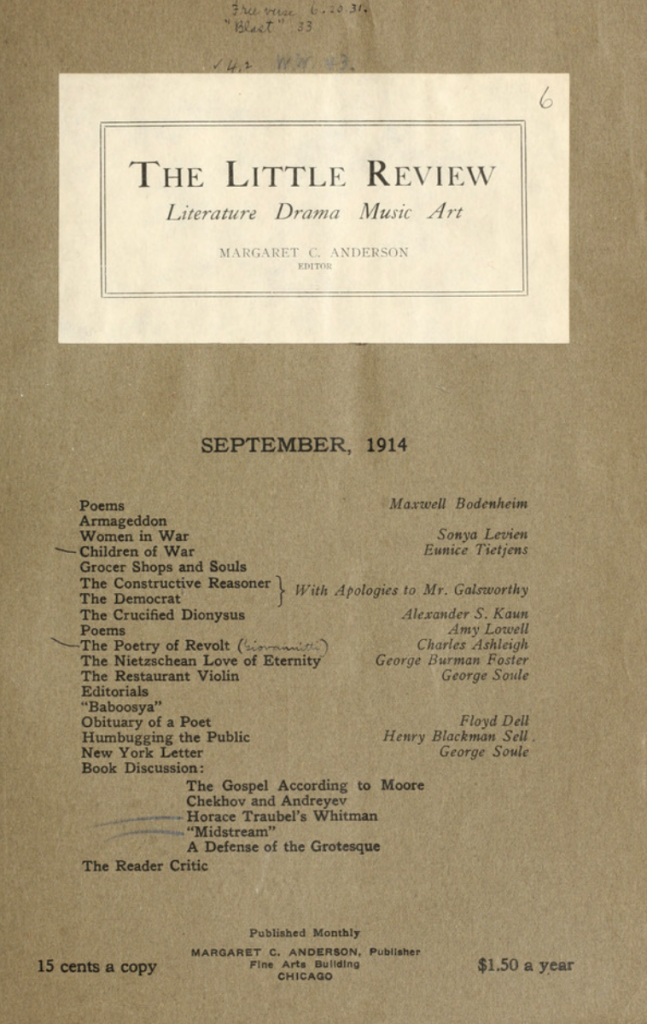

Anderson was born in Indianapolis in 1886 and moved to Chicago in 1908, where she served on the staff of The Dial—a magazine of criticism and literature that would become a major outlet for modernist writers—and as a book critic for the Chicago Evening Post before founding The Little Review as a monthly magazine in 1914. She began the first issue, which was published in September of that year, with this treatise: “Books register the ideas of an age; this is perhaps their chief claim to immortality. But much that passes for criticism ignores this aspect of the case and deals merely with a question of literary values. To be really interpretative—let alone creative—criticism must be a blend of philosophy and poetry.”

Over the magazine’s fifteen-year history, Anderson would, alongside editors Jane Heap and Ezra Pound, publish poems and ideas by both prominent and fledgling modernist writers from the Chicago area and around the world. The first issue featured poems by Maxwell Bodenheim and Amy Lowell; later issues featured new work by Djuna Barnes, T. S. Eliot, Dorothy Richardson, Carl Sandburg, Gertrude Stein, W. B. Yeats and—infamously—James Joyce, whose novel Ulysses was first serialized in The Little Review’s pages. Anderson noted in My Thirty Years’ War, “Practically everything The Little Review published during its first years was material that would have been accepted by no other magazine in the world at the moment. Later all the art magazines wanted to print our contributors and, besides, pay them.”

Over the magazine’s fifteen-year history, Anderson would, alongside editors Jane Heap and Ezra Pound, publish poems and ideas by both prominent and fledgling modernist writers from the Chicago area and around the world. The first issue featured poems by Maxwell Bodenheim and Amy Lowell; later issues featured new work by Djuna Barnes, T. S. Eliot, Dorothy Richardson, Carl Sandburg, Gertrude Stein, W. B. Yeats and—infamously—James Joyce, whose novel Ulysses was first serialized in The Little Review’s pages. Anderson noted in My Thirty Years’ War, “Practically everything The Little Review published during its first years was material that would have been accepted by no other magazine in the world at the moment. Later all the art magazines wanted to print our contributors and, besides, pay them.”

The Little Review is known both for its role in solidifying this modernist coterie and for its early championing of a variety of socio-political causes, including anarchism, gay rights, and workers’ rights. In the March 1915 issue, Anderson published what biographer Holly Baggett calls, according to the Chicago Tribune, “the first editorial by a lesbian on the treatment of gay people.” Anderson wrote, “With us love is just as punishable as murder or robbery.” This eschewing of the political mainstream likely contributed to a drop in advertising and funding, which, in turn, brought on what Christopher J. La Casse in a 2015 Criticism article described as “economic hard times: from withdrawn subsidies, coverless issues, disconnected telephones, and bad checks to a brief period during which Anderson consolidated her office and residence under tents on the shores of Lake Michigan.” Over the course of 1915 and 1916, the formerly 64-page publication dwindled to 28 pages, and slowly, the magazine began drifting away from its political stance.

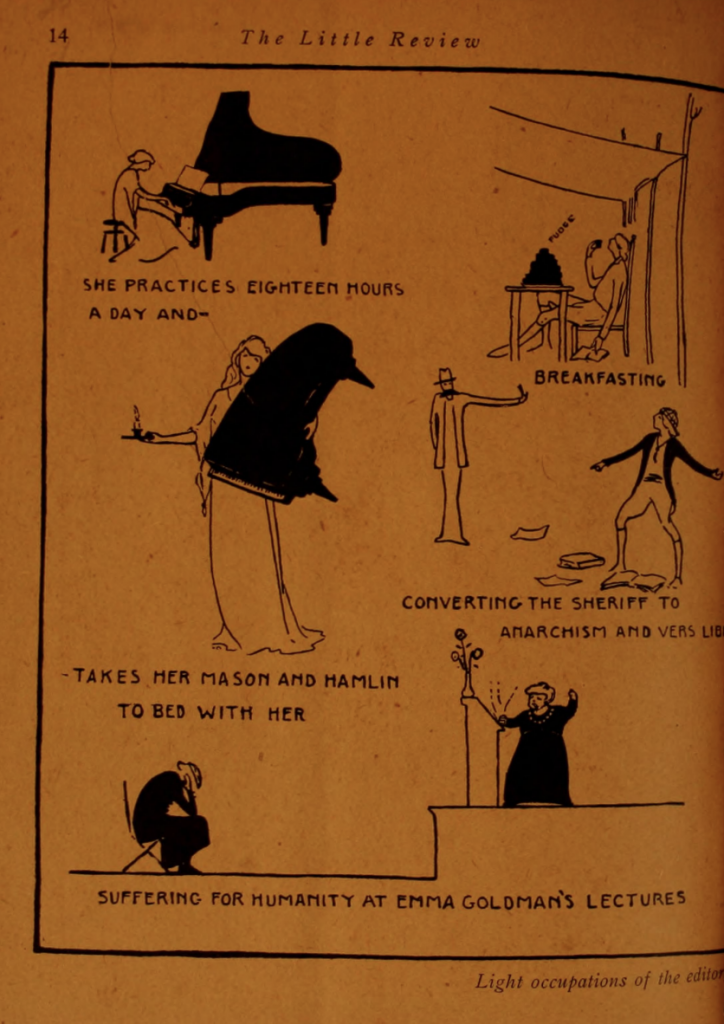

In 1916 Anderson met Jane Heap, who was active in Chicago’s art and theater scene. Heap, who served as an editor of and advisor to The Little Review under the pseudonym J. H. and became Anderson’s romantic partner for several years, also worked on the design and typography of the magazine and helped forefront the work of visual artists within its pages, including that of sculptor Constantin Brancusi. She also contributed a cartoon to an otherwise mostly blank issue in September 1916, which began with this controversial note from Anderson: “The Little Review hopes to become a magazine of Art. The September issue is offered as a Want ad.”

In 1916 Anderson met Jane Heap, who was active in Chicago’s art and theater scene. Heap, who served as an editor of and advisor to The Little Review under the pseudonym J. H. and became Anderson’s romantic partner for several years, also worked on the design and typography of the magazine and helped forefront the work of visual artists within its pages, including that of sculptor Constantin Brancusi. She also contributed a cartoon to an otherwise mostly blank issue in September 1916, which began with this controversial note from Anderson: “The Little Review hopes to become a magazine of Art. The September issue is offered as a Want ad.”

Also in 1916, as paper prices increased because of the war, The Little Review announced “possibly the first prize extended to free verse”: the Vers Libre Contest, made possible by an individual donation and judged by William Carlos Williams, Zoë Aikens, and Helen Hoyt. The contest received 202 submissions, 32 of which were disqualified for adhering to a set form, and the winning poems—which included H.D.’s “Sea Poppies” and Richard Aldington’s “Stream”—were featured in the April 1917 issue.

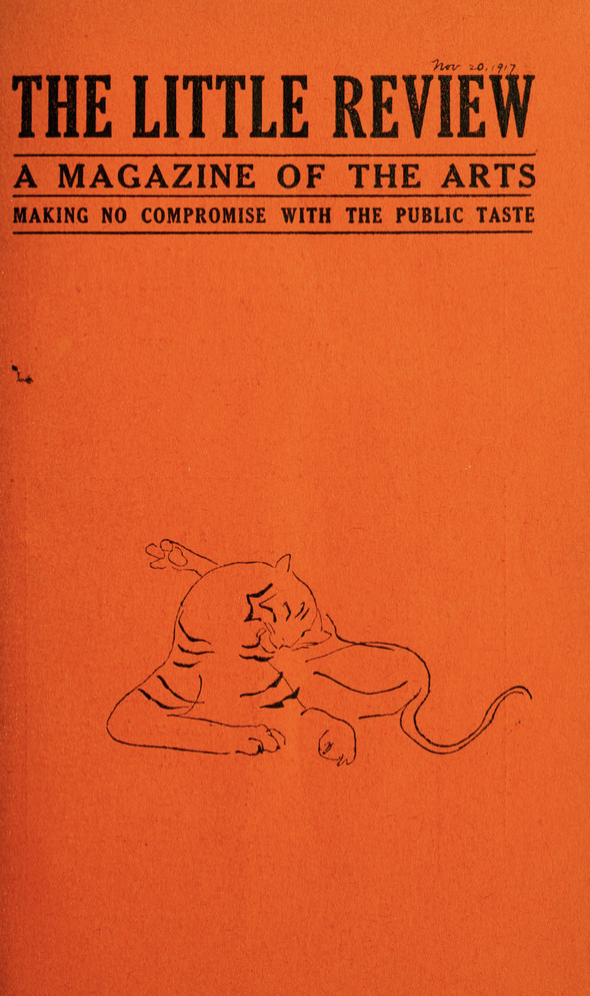

Anderson and Heap moved to New York City in 1917, and that summer, Anderson added a subtitle to The Little Review—Making No Compromise with the Public Taste—and brought Ezra Pound on as foreign editor. Pound wrote in an introduction to the May 1917 issue that he had accepted the post because “I wished a place where the current prose writings of James Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, T. S. Eliot, and myself might appear regularly, promptly, and together, rather than irregularly, sporadically, and after useless delays.” Over the course of his two-year editorship, Pound published literary criticism and the work of some new contributors, and he also worked to pivot the magazine’s reputation to that of a highbrow, selective space. Under his leadership, The Little Review benefited from new patronage and became the first place of publication for more major modernist voices, including those of T. S. Eliot and W. B. Yeats. By 1918, the issues had expanded again to 64 pages, and the circulation had risen from 1,000 to 3,000.

When Pound came on as foreign editor, James Joyce wrote a note that was printed in the magazine’s June 1917 issue: “I am very glad to hear about the new plans for The Little Review and that you have got together so many good writers as contributors. I hope to send you something very soon.” He did, and in 1918, The Little Review began serializing Ulysses in its monthly issues. Pound’s role as London foreign editor was largely taken over by John Rodker in May 1919; in a letter to Anderson, printed in My Thirty Years’ War, Pound explained, “Chère amie, I am, for the time being, bored of being any kind of an editor.” The Little Review continued printing Ulysses through December 1920, and during this time the Post Office seized and burned four separate issues for indecency. In 1921, Anderson and Heap were tried and found guilty on obscenity charges. They were each charged $50.

When Pound came on as foreign editor, James Joyce wrote a note that was printed in the magazine’s June 1917 issue: “I am very glad to hear about the new plans for The Little Review and that you have got together so many good writers as contributors. I hope to send you something very soon.” He did, and in 1918, The Little Review began serializing Ulysses in its monthly issues. Pound’s role as London foreign editor was largely taken over by John Rodker in May 1919; in a letter to Anderson, printed in My Thirty Years’ War, Pound explained, “Chère amie, I am, for the time being, bored of being any kind of an editor.” The Little Review continued printing Ulysses through December 1920, and during this time the Post Office seized and burned four separate issues for indecency. In 1921, Anderson and Heap were tried and found guilty on obscenity charges. They were each charged $50.

The Little Review survived the Ulysses trials and was published through 1929, though Anderson stepped away in 1924, as she “felt that we had approached its logical conclusion.” Heap took over as editor in the 1920s from Paris, where she and Anderson both lived despite being separated. The magazine continued under Heap’s leadership until 1929, when, as Anderson wrote in My Thirty Years’ War, “Jane agreed with me at last that The Little Review should be brought to a close.” Anderson went on to publish numerous autobiographies and memoirs before she died in Le Cannet, France, in 1973. Heap lived in London for many years and died there in 1964. According to her New York Times obituary, published on June 23, 1964, when The Little Review was shuttered in 1929, critic Louis Kronenberger wrote, “The magazine which first gave us Ulysses represents that struggle for both free speech and significant new material which, though it left behind an enormous amount of waste, left also the old gods shattered, the old conventions powerless.”