As part of our mission to support, celebrate, and promote literary magazines and presses, we showcase in this series short essays about the many publishers that have contributed to the collective story of independent publishing in our country.

In the decades and years leading up to the August 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment, granting women the right to vote, numerous journals and newspapers served as forums for women to share poems, satires, essays, interviews, and other literary rallying cries around women’s suffrage. “For every woman who dared stand on a podium and address an audience about the importance of enfranchising women,” Mary Chapman and Angela Mills explained in the introduction to Treacherous Texts: U.S. Suffrage Literature, 1846–1946 (Rutgers University Press, 2011), “many others wrote popular literary works in support of suffrage. Some were amateurs moved to write because they cared so deeply about the Cause; others were established professional writers, many of whom we now recognize as central figures in the American literary canon.”

In the decades and years leading up to the August 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment, granting women the right to vote, numerous journals and newspapers served as forums for women to share poems, satires, essays, interviews, and other literary rallying cries around women’s suffrage. “For every woman who dared stand on a podium and address an audience about the importance of enfranchising women,” Mary Chapman and Angela Mills explained in the introduction to Treacherous Texts: U.S. Suffrage Literature, 1846–1946 (Rutgers University Press, 2011), “many others wrote popular literary works in support of suffrage. Some were amateurs moved to write because they cared so deeply about the Cause; others were established professional writers, many of whom we now recognize as central figures in the American literary canon.”

Poet and journalist Alice Dunbar Nelson agreed; in a suffrage-themed issue of The Crisis, she wrote, “It is a significant fact that the American and English women who are now doing the real work in literature—not necessarily fiction—are the women who are most vitally interested in universal suffrage.”

Among the publications for suffrage literature were Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis’s The Una, founded in 1853; Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony’s The Revolution, founded in 1868; The Woman’s Journal, which ran for 61 years in various formats and was first published in 1870 by Lucy Stone; and Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Fore-Runner, in print from 1909 through 1916. “Through these print cultural networks,” Chapman and Mills continued, “rhetorically powerful literary works reached millions of Americans and persuaded many of them not only to support the movement but also, in some cases, to raise funds for the campaign.”

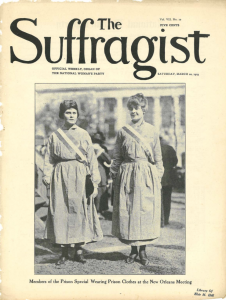

Another major publication in this lineage was The Suffragist, a weekly newspaper that ran from late 1913 through early 1921. The Suffragist served as the official organ of the Congressional Union for Women’s Suffrage, founded earlier in 1913 by Alice Paul—who, with Lucy Burns, had recently organized a march on Washington on the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Paul began The Suffragist’s first issue with a Foreword: “We send into the world today a new paper,” the primary purpose of which was “to aid in securing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States enfranchising the women of the whole country.”

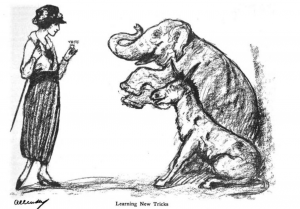

Over the eight years it remained in publication, The Suffragist—edited first by Rheta Childe Dorr, author of the 1911 essay collection What 8,000,000 Women Want, and later by Lucy Burns, Sue Shelton White, and Edith Houghton Hooker—did just that, providing a community where women’s rights activists could converse freely and helping to legitimize discussion of a potential suffrage amendment. Its weekly issues featured poems by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Katharine Fisher, and other suffragist poets; interviews of prominent women; considerations of women’s changing roles in domestic spaces and the workplace; discussions of feminism in foreign countries; and other pieces at the intersection of literature and women’s rights. In addition, The Suffragist is remembered for its political cartoons, many of which were drawn by Nina Allender, who told the Christian Science Monitor, “Political cartooning gives you a sense of power that nothing else does.”

However, Susan Ware writes in Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote (Belknap Press, 2019), Allender’s cartoons “often reinforced class and race prejudices” and were “a mirror not just of the racism of the suffrage movement but of the racial and class hierarchies of Progressive-era American society.” This was also true, more generally, of The Suffragist, which prioritized the voting rights of white women; while the publication was groundbreaking in many ways, it didn’t embody the interest in “universal suffrage” Nelson spoke of in The Crisis. Many of the activists published in its pages, including Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Margaret Sanger, are remembered today both for their groundbreaking work and for their racism.

Soon after the 19th Amendment was ratified, granting the right to vote to white women but still leaving many Black women, particularly in the South, disenfranchised, The Suffragist began powering down. Its final issues celebrated the movement’s victory, explored topics related to feminism more broadly, and considered what should come next. In the 1921 essay “Art and Women’s Freedom,” sculptor Gertrude Boyle wrote, “For ages man, with rare exception, has monopolized the world of art. But the time has at last come when another phase of life must find expression through art—woman-engendered art. The voice of the female soul must rise high and clear above the discords of the day—above the deadening grind of the wheel of things.”

Soon after the 19th Amendment was ratified, granting the right to vote to white women but still leaving many Black women, particularly in the South, disenfranchised, The Suffragist began powering down. Its final issues celebrated the movement’s victory, explored topics related to feminism more broadly, and considered what should come next. In the 1921 essay “Art and Women’s Freedom,” sculptor Gertrude Boyle wrote, “For ages man, with rare exception, has monopolized the world of art. But the time has at last come when another phase of life must find expression through art—woman-engendered art. The voice of the female soul must rise high and clear above the discords of the day—above the deadening grind of the wheel of things.”

And in the publication’s final issue, Freda Kirchwey—who would go on to edit The Nation for more than twenty years—looked to the future of this avenue of publishing: “The fact is that women, whether they have worked for the vote” or not, “are discontented. Some want wider political rights, some want wider legal and industrial rights, all want wider human rights…. For this reason, above all others, I believe we must have a new sort of women’s magazine.”