Kaya Press is a finalist for CLMP’s 2022 Constellation Award, given to honor an independent literary press that is led by and/or champions the writing of people of color, including Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian American & Pacific Islander (AAPI) individuals for excellence in publishing.

We spoke with Publisher and Editor Sunyoung Lee and Managing Editor Neelanjana Banerjee in this Member Spotlight.

What is the history behind Kaya Press? When was it founded and what is its mission?*

HISTORY IS UNEARTHED in Southampton. Vents of methane gas jet out of cracks in the dirt beneath the tract homes that stretch from the straits up past our house to Lake Herman. Along Rose Drive, the air clings to swing sets like the spindly whites of old eggs. The earth opens up and swallows entire backyards. Foundations we never had cause to question are now cleaved and splintered. My friend, who has grown up in an old Victorian down by the waterfront, laughs and says, We all knew that there was a landfill. I dumped stuff there with my dad once or twice. The developers covered it up with dirt and built on top of it.

HISTORY IS UNEARTHED in Southampton. Vents of methane gas jet out of cracks in the dirt beneath the tract homes that stretch from the straits up past our house to Lake Herman. Along Rose Drive, the air clings to swing sets like the spindly whites of old eggs. The earth opens up and swallows entire backyards. Foundations we never had cause to question are now cleaved and splintered. My friend, who has grown up in an old Victorian down by the waterfront, laughs and says, We all knew that there was a landfill. I dumped stuff there with my dad once or twice. The developers covered it up with dirt and built on top of it.

—from American Canyon by Amarnath Ravva

ALWAYS ALWAYS ALWAYS

YOUR LEFT FOOT doesn’t speak. YOUR RIGHT FOOT has no fixed idea.

THE NEXT FOOT STEP doesn’t catch flies.

THE DELUSION OF SPEED IS OVERTURNED. BY WHOM?

BY WALKING

The Futurist is dead. Of What? Of WALKING

A soldier becomes a poet or farmer. Because of What? WALKING

The solar fire licks your skin. Who invented it? WALKING

Someone walks on your feet. It’s YOU

—from “Walking East Manifesto” in City of the Future by Sesshu Foster (winner of the Firecracker Award for Poetry)

___________

* Kaya Press was founded in 1994 by Soo Kyung Kim, a postmodern Korean writer, and was originally intended to house a journal of Korean literature-in-translation, which eventually morphed into Muae, a spirited anthology highlighting the newest in Asian Pacific American writing that Library Journal named one of “The Best Magazines of 1995.” The 1997 Asian economic collapse meant that Kim was no longer able to support Kaya, so around that time editor Sunyoung Lee and managing editor Juliana Koo managed to survive—and thrive—by turning Kaya into a nonprofit.

Lee managed to keep Kaya afloat through sheer stubbornness—and carried the press with her and continued to put books out—while she moved west to get an MFA in poetry at UC Irvine, and then moved to Berkeley, California. Kaya had a reemergence when it was officially housed in the American Studies and Ethnicity Department at the University of Southern California (USC) in 2011, so this fall it will have been based in Los Angeles for ten full years. Neelanjana Banerjee joined the staff in 2012, and we are moving toward a third decade with lots of excitement.

Lee managed to keep Kaya afloat through sheer stubbornness—and carried the press with her and continued to put books out—while she moved west to get an MFA in poetry at UC Irvine, and then moved to Berkeley, California. Kaya had a reemergence when it was officially housed in the American Studies and Ethnicity Department at the University of Southern California (USC) in 2011, so this fall it will have been based in Los Angeles for ten full years. Neelanjana Banerjee joined the staff in 2012, and we are moving toward a third decade with lots of excitement.

We really see our mission as publishing books that will inspire people, more than anything. We see our work at Kaya Press as a never-ending (more than 25 years and counting!) effort to highlight the motherlode of wisdom available from API writers. Especially in this time of trying to highlight and uplift API stories, it seems to us that the best way to represent our press and the political approach we take to publishing is to foreground the words of our authors. The insights to be found in their writings is after all the reason why we do the work that we do.

Why is it important to foster this dedicated space for cutting-edge work by Asian and Pacific Islander diasporic writers?*

It was not enough to live among the objects and habits of another person; she needed to sit down with someone over a cup of hot tea and bean cake. She tried to distract herself by reinvesting her attention towards fixing things around the house: darning the young man’s socks, washing the blinds, the windows, leaving him dinner twice a week. But still she missed the company of friends.

—from “The Woman In the Closet” in Last of Her Name by Mimi Lok (winner of the PEN America Literary Award for Debut Short Story Collection)

Mai-Lan Phan is Vietnamese.

Jared Shimabukuro is Okinawan.

Judy-Ann Katsura is Japanese.

Stephen Bean is Caucasian.

Loata Faalele is Samoan.

Caroline Macadangdang is one-fourth Filipino, one-fourth Spanish, one-fourth Chinese, one-eighth Hawaiian, one-sixteenth Cherokee Indian, and one-sixteenth Portuguese-Brazilian.

And the rest tell Mrs. Takemoto, who has gone row by row asking them their ethnicity, that they are Filipinos, except for Nelson Ariola, who says he is an American although he is as Filipino as any Filipino can be.

“No, Nelson,” Mrs. Takemoto says. “Your nationality is American, but your ethnicity is Filipino.”

“Yeah, Nelson, “ Katrina Cruz interrupts. “You was born a Filipino, and you goin’ die a Filipino.”

“Shut up, Katrina,” Nelson says.

“You shut up, Nelson,” she says. “What makes you think you not a Filipino?”

“Because I was born here,” he says.

“So? Me, too,” she argues.

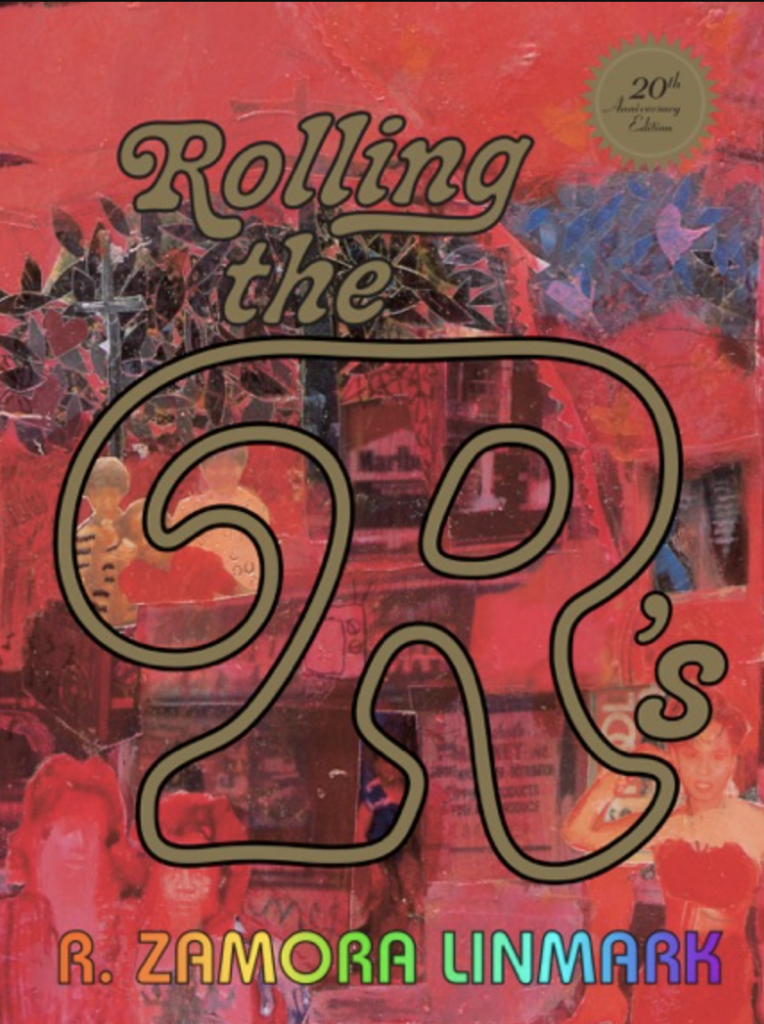

— from Rolling the R’s by R. Zamora Linmark

___________

* When Kaya was founded in the 1990s, it was really important for us to hold up experimental narratives and texts—like R. Zamora Linmark’s Rolling the R’s, which was about a group of Filipino kids coming of age in 1970s Hawaii, or Sesshu Foster’s City Terrace Field Manual, where Foster maps his own mixed-race identity onto the shifting identities of East Los Angeles—against the monolithic stories of Asian American immigrants who were trying so hard to assimilate into mainstream American culture or only interacting with White America. But I think our work has always been primarily about finding and giving a platform to voices that, as we mentioned in our mission, have the potential to inspire readers to learn more, to create more, and to make change.

* When Kaya was founded in the 1990s, it was really important for us to hold up experimental narratives and texts—like R. Zamora Linmark’s Rolling the R’s, which was about a group of Filipino kids coming of age in 1970s Hawaii, or Sesshu Foster’s City Terrace Field Manual, where Foster maps his own mixed-race identity onto the shifting identities of East Los Angeles—against the monolithic stories of Asian American immigrants who were trying so hard to assimilate into mainstream American culture or only interacting with White America. But I think our work has always been primarily about finding and giving a platform to voices that, as we mentioned in our mission, have the potential to inspire readers to learn more, to create more, and to make change.

Today, we continue to be interested in books that can do this work, like the CLMP Firecracker Award–winning poetry collection by Truong Tran, book of the other, which is a deep look into the lived realities of anti-Asian racism; and also a forthcoming book, We Make Constellations of the Stars by multiethnic artist and food justice worker Sita Kuratomi Bhaumik, which maps her path to becoming an artist through community, identity, food, and more. We believe that books can facilitate dreaming and creativity and maybe even the desire for greater empathy and humanity.

Can you tell us about the class Asian American Publishing with Kaya Press offered at UCLA? What is the Publishing Project series produced by this class’s students?*

Most of the graves we walk by are shaped like matchboxes turned on end. Stylistically, they’re predominantly western. But there’s something distinctly meager about them all. It’s an aesthetic that I just don’t appreciate. And my feelings are only aggravated by the fact that everyone wants to have the same trendy style of headstone—this is my first reaction, at least, until I remember that this isn’t necessarily a matter of style or fashion, but rather an aesthetic that cemetery policy has forced everyone into.

Still, it deserves consideration. There should be some room for individuality, in a gravestone. Part of the fun of visiting a cemetery is walking around and seeing all the different shapes of graves. Variety is the spice of something, and these headstones seem so small and pathetic. Something about it just feels wrong.

— from I Guess All We Have Is Freedom by Akasegawa Genpei (translated by Matthew Fargo)

___________

* I’ve been teaching Asian American Creative Writing classes in the UCLA Asian American Studies Department for several years. My creative writing students are always interested in interning, so I approached the department at UCLA to create a class that would allow students to learn about publishing and intern directly with Kaya Press. Along with this, I wanted students to work on their own publishing projects to give them the full experience of acquiring work, editing, and producing their own publication. I see the course as a way for students to discuss and critique the overwhelming White Supremacy of mainstream publishing and work together—as Kaya Press does—to make an intervention in that system. I am also now teaching in the Literary Editing and Publishing Program at the University of Southern California, the university where Kaya Press is based, so can really center my work on building the next generation of people who are working in publishing and thinking about literary arts.

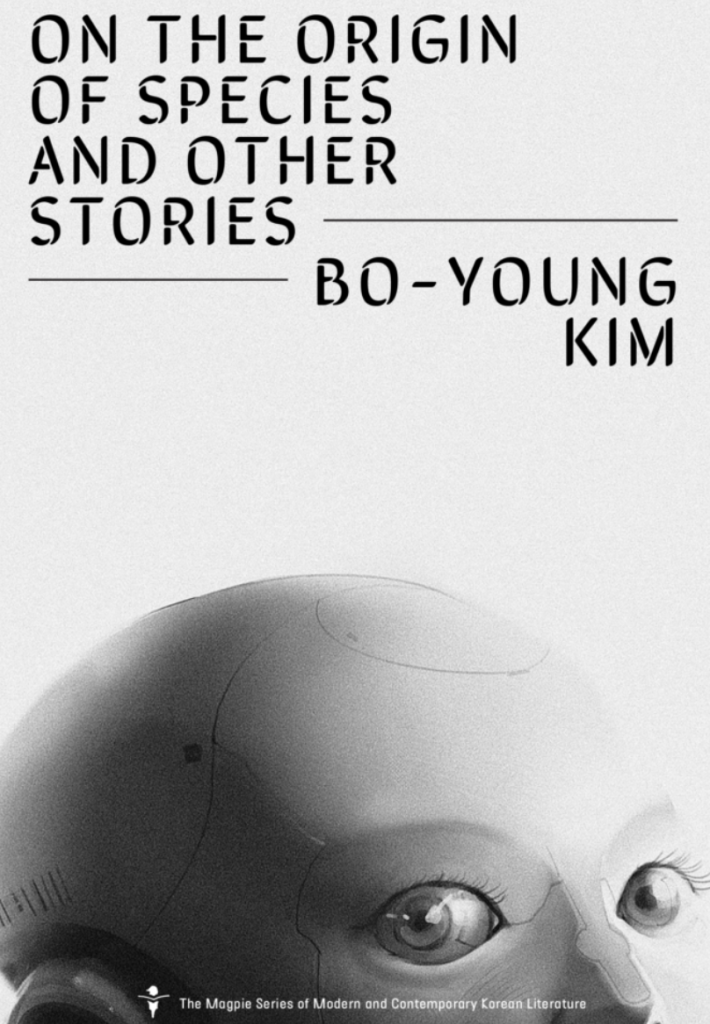

Bo-Young Kim’s collection, On the Origin of Species and Other Stories—one of her first translated into English—was published in May 2021 and was longlisted for the National Book Award in Translation. Can you tell us about this book and some of your other recent titles?*

Looking puzzled, the traveler stammered, “He figured out I’m a woman. Our conversations contained no hint of my gender, nor is it something he could have gotten from context.”

Looking puzzled, the traveler stammered, “He figured out I’m a woman. Our conversations contained no hint of my gender, nor is it something he could have gotten from context.”

“He didn’t figure it out. You just think he did.”

The traveler’s eyes widened.

“It didn’t matter whether he got it right or wrong,” she continued. “If he was wrong, you’d simply have corrected him and moved on. And your denial would have been received as an update. Anyway, he had a 50/50 chance of answering correctly. There are other examples: Something’s bothering you, isn’t it? And, What’s on your mind? And, Anything exciting going on these days?”

The traveler started to object but nothing came out.

—from “Scripter” in On the Origin of Species and Other Stories by Bo-Young Kim

___________

* On the Origin of Species and Other Stories is the first collection of science-fiction stories that we’ve ever published—and we are thrilled that it’s from the pioneering science-fiction writer Bo-Young Kim. It’s so interesting to see how this stunning collection of stories continues to expand what science fiction and fantasy can be, especially from a Korean point of view. We were so excited that Kim’s work, and that of her translators Sora Kim-Russell and Jeongmin Lee-Comfort, received recognition from the National Book Awards committee. This was the second title in our Magpie Series, an imprint focusing on Korean literature in translation, and we were very excited to publish another title in spring 2023 from the author Djuna, who is known exclusively as an online persona, called Everything Good Dies Here: Tales from the Linker Universe and Beyond.

Can you tell us about the newly announced imprint Ink & Blood with the Diasporic Vietnamese Artist Collective and in partnership with Viet Thanh Nguyen? Why this is important to Kaya Press?

Nothing could force our language to praise the beauty of their women nor the cunning of their offspring. When traveling merchants and rag-pickers passed through the barbarians’ gates, our language followed them to their resting quarters. While they slept, she smuggled a few phrases in casks of fish oil. These made their way back to our village, one braid at a time, word by word, letter by letter.

It is our hope that we will one day salvage enough to write all that has happened since our language was lost to us, and then to rewrite everything again as though it had never happened.

— “Captivity Narrative” from Mouth by Lisa Chen

_______

* Ink & Blood is the realization of a long-held desire to share Kaya’s publishing experience, built up over more than 25 years, with other editors and organizations by helping them to create their own imprints. It’s actually the second imprint we’ve created—our first, the Magpie Series, focuses on Korean literature in translation and was launched with Readymade Bodhisattva, the first ever English-language anthology of South Korean science fiction. Working on these new imprints is pushing us to actualize our ideas about how publishing is political—by which we mean, it’s a means of pushing people’s expectations about what books can do, what stories can do, what language can do.

* Ink & Blood is the realization of a long-held desire to share Kaya’s publishing experience, built up over more than 25 years, with other editors and organizations by helping them to create their own imprints. It’s actually the second imprint we’ve created—our first, the Magpie Series, focuses on Korean literature in translation and was launched with Readymade Bodhisattva, the first ever English-language anthology of South Korean science fiction. Working on these new imprints is pushing us to actualize our ideas about how publishing is political—by which we mean, it’s a means of pushing people’s expectations about what books can do, what stories can do, what language can do.

Viet Thanh Nguyen has always been a huge supporter of Kaya, and he became a member of our Board of Directors when we moved to Los Angeles. He’s also a founding member of the Diasporic Vietnamese Artist Collective (DVAN), which grew out of a writing group he created with Isabelle Pelaud. The primary catalyst for this collaboration between Kaya and DVAN was an angel donor, Stephen CuUnjieng, who first suggested that we take concrete steps towards working together organizationally—resulting in the Ink & Blood imprint, which will focus on diasporic Vietnamese writers in translation. CuUnjieng then provided generous funding to help seed the project. The first book to be translated in the Ink and Blood series will be Line Papin’s The Girl Before Her, which will be published this spring.