As part of our mission to support, celebrate, and promote literary magazines and presses, we showcase in this series short essays about the many publishers that have contributed to the collective story of independent publishing in our country.

In the Autumn 1926 edition of The Yale Review, Virginia Woolf wrote, “It would not be in the least surprising to discover, on the day of judgment when secrets are revealed and the obscure is made plain, that the reason why we have grown from pigs to men and women… and erected some sort of shelter and society on the waste of the world, is nothing but this: we have loved reading.”

In the Autumn 1926 edition of The Yale Review, Virginia Woolf wrote, “It would not be in the least surprising to discover, on the day of judgment when secrets are revealed and the obscure is made plain, that the reason why we have grown from pigs to men and women… and erected some sort of shelter and society on the waste of the world, is nothing but this: we have loved reading.”

When Woolf penned this, in her now-iconic essay “How Should One Read a Book?,” The Yale Review was near the height of its print circulation, which peaked at 18,000 before the 1929 stock market crash. This literary journal was already more than a century old, though, and had undergone several major changes. A group of Yale University faculty members had founded the publication in 1819 as The Christian Spectator, dedicated to promoting discussion and reflection on religious doctrines and ideas. In 1829, The Christian Spectator became The Quarterly Christian Spectator, and in 1843 it changed more dramatically, to The New Englander, the first volume of which contained an article about the post office system, an article arguing in favor of capital punishment, and a piece on modern German philosophy. In 1885, the publication transformed again into The New Englander and Yale Review—and again in 1892, into The Yale Review: A Quarterly Journal of History and Political Science, the first two articles of which were titled “Probable Effects of the Existing Silver Law” and “The Dissolution of the Standard Oil Trust.”

In October 1911, the Yale Review transformed a fifth time, into the literary incarnation we know today, which was originally known as the New Series and was edited for the next thirty years by Wilbur Cross, an English professor who went on to serve as the governor of Connecticut from 1931 to 1939. The New Series featured work by many notable, or soon-to-be notable, authors in its first years, including Edith Wharton, Witter Bynner, Robert Browning, Amy Lowell, Archibald MacLeish, Robert Frost, Edgar Lee Masters, Winifred Letts, Alfred Noyes, Sara Teasdale—and, of course, Virginia Woolf, who contributed nine essays to The Yale Review between 1926 and 1938.

In October 1911, the Yale Review transformed a fifth time, into the literary incarnation we know today, which was originally known as the New Series and was edited for the next thirty years by Wilbur Cross, an English professor who went on to serve as the governor of Connecticut from 1931 to 1939. The New Series featured work by many notable, or soon-to-be notable, authors in its first years, including Edith Wharton, Witter Bynner, Robert Browning, Amy Lowell, Archibald MacLeish, Robert Frost, Edgar Lee Masters, Winifred Letts, Alfred Noyes, Sara Teasdale—and, of course, Virginia Woolf, who contributed nine essays to The Yale Review between 1926 and 1938.

The Yale Review is considered the country’s oldest literary magazine in continuous publication, as well as the oldest literary quarterly in the United States. In 1931, the New York Times reported, “What can be more obvious than that the ever-mounting speed of present-day life has rendered obsolete the old leisurely journalism of the quarterlies?” However, the article concluded, “All the signs are against the quarterly magazine until a publication like The Yale Review comes along to show that for a good quarterly there is still plenty of room.”

Despite this evidence of its importance, during and after the Great Depression The Yale Review’s circulation remained lower than its 1929 peak, falling to 4,000 by the late 1980s. Then, in July 1990, Yale University announced that it would cease production on the journal. Both the university community and the wider literary community took notice, and after a broadly circulated petition, an angry letter from John Hersey to the Yale alumni magazine, and an alumni committee founded in protest, the university rescinded this plan. The New York Times reported, “The statement from the university president, Benno C. Schmidt Jr., comes after a bitter and public struggle to save the quarterly by many literary figures and alumni, along with a more private debate over the direction the quarterly should take.”

The poet J. D. McClatchy, who had formerly served as the poetry editor, took on the role of editor. In an interview at the time, McClatchy said, “More was at stake than just a magazine…. There was also the commitment on the part of universities, not just Yale, but others, to finance and support these kinds of intellectual vehicles.” McClatchy served for nearly thirty years, and according to the Yale Daily News, during this time he “expanded its literary content, revamped its finances, and was instrumental in raising a permanent endowment that continues to support its work today.”

The poet J. D. McClatchy, who had formerly served as the poetry editor, took on the role of editor. In an interview at the time, McClatchy said, “More was at stake than just a magazine…. There was also the commitment on the part of universities, not just Yale, but others, to finance and support these kinds of intellectual vehicles.” McClatchy served for nearly thirty years, and according to the Yale Daily News, during this time he “expanded its literary content, revamped its finances, and was instrumental in raising a permanent endowment that continues to support its work today.”

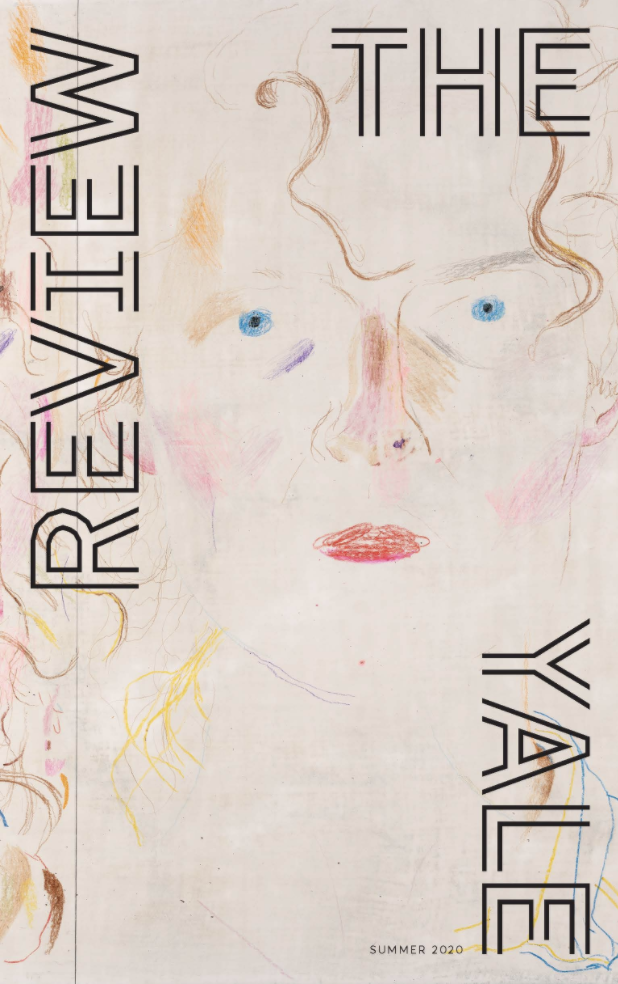

Harold Augenbraum, who took over as acting editor from McClatchy’s 2017 retirement to 2019, told the Yale Daily News, “Every few decades there is a reinvention of The Yale Review in order to keep it current and interesting to the culture of the time.” True to this pattern, The Yale Review is currently in the process of another transformation, which officially began in 2019 on the 200th anniversary of the journal’s founding, when Megan O’Rourke became its next editor. The Summer 2020 issue unveiled a full redesign by Pentagram, and O’Rourke now publishes web-exclusive content and plans to introduce a podcast.

O’Rourke addressed the importance of The Yale Review continuing to adapt and shift in an interview with Aaron Robertson for LitHub: “With the literary landscape changing dramatically, The Yale Review, like many print journals, has meaningful questions to answer about how to exist on other platforms. As the Review moves online… I want to make sure we are meaningfully adding to the conversation at large. My intention, at the moment, is to expand slowly in ways that build community and lead to more immediate engagement with our contributors and readers.”

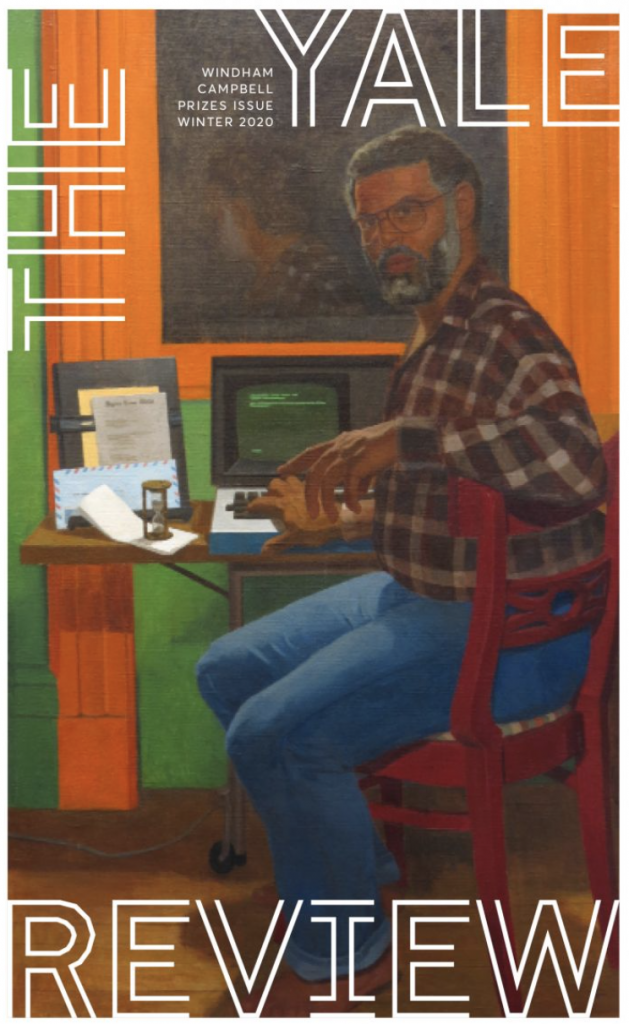

Most recently, The Yale Review has provided a forum for the literary community to celebrate some of its own during the current COVID-19 crisis. When festivities around the 2020 Windham-Campbell Prizes—Yale University–based prizes offering winners an unrestricted grant of $165,000 to support their writing—were cancelled due to the pandemic, The Yale Review’s next issue became a version of the Windham-Campbell Festival in print. In his introduction to The Yale Review Windham-Campbell Prizes Issue, Director Michael Kelleher writes, “What you hold in your hands is not a festival, but it represents some part of us and some part of what we hope a festival might be: a celebration, a gift, sent from us to you, with hopes that we will see you in person again next year.”