by Kevin Breen

This article is the third in a biweekly series examining AI and its implications for publishers and authors.

One of publishers’ most pressing concerns is how to identify content generated by artificial intelligence. As generative AI (genAI) has reached wider audiences and been trained on more data, that task has proven more difficult. That’s a big problem for the publishing world. Whether you’re for or against genAI, your stance quickly becomes moot when you can’t tell whether a manuscript has been drafted using ChatGPT or a cover design has come from a real-life human artist. In this article, we’ll look at generative AI: its history, what it looks like today, and its current hallmarks. Then, we’ll walk through how to identify genAI content, both on your own and with widely available detection tools.

The early days of genAI

Most of us were introduced to today’s genAI around 2019 and 2020. Notably, OpenAI’s ChatGPT-2 was viewed as a significant leap forward in language modeling. As the Verge’s James Vincent noted back in early 2019, “writing [ChatGPT-2] produces is usually easily identifiable as non-human.” AI image generators gave themselves away in equally obvious ways: reproducing facsimiles of the Getty watermark, generating six-fingered hands, and producing other uncanny photo replicas. In short, genAI was a work-in-progress, prone to errors and obvious “hallucinations.”

GenAI nowadays

Technology has come a long way in six years, and large language models have improved dramatically. Users now have free access to ChatGPT-4. GenAI images look increasingly realistic. And genAI tools have been embedded in common publishing software programs like Adobe Photoshop, Acrobat, and Illustrator. So how can authors, publishers, and readers identify generative AI when it crops up in their professional lives?

GenAI images

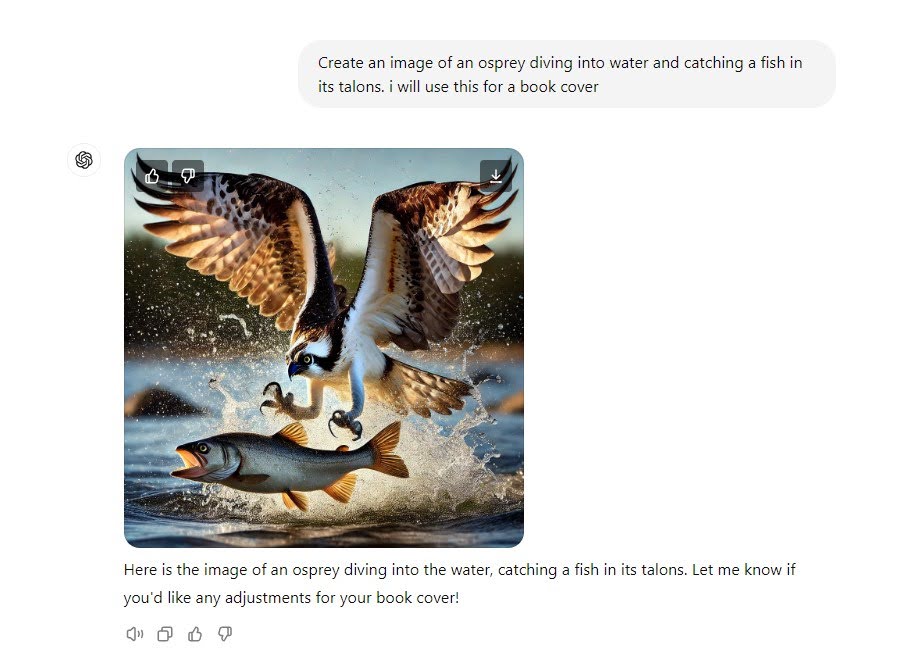

Generally speaking, images generated using AI share some characteristics. They tend to muck up precise details, like the proportions of a torso to a neck, text on someone’s graphic tee in the crowd, or the number of teeth in a smile. Notably, ChatGPT/DALL-E will typically produce a pixel-perfect image, one that renders in extremely high resolution. Here’s an example of an osprey image I asked ChatGPT to spin up:

My initial prompt, asking ChatGPT to create a cover-worthy image

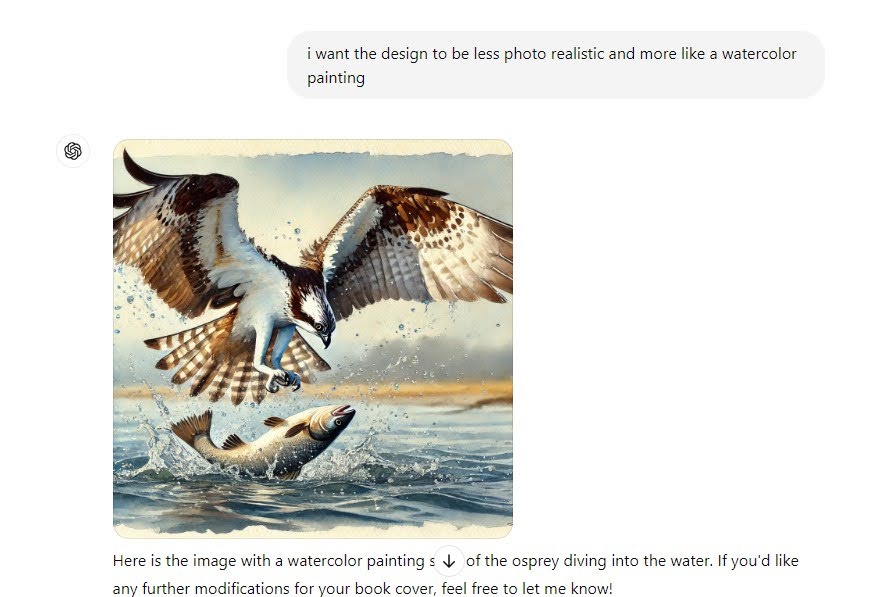

These are the kinds of images we tend to associate with genAI: incredibly high resolution, a blend of photo-realism and cartoonish traits, plus some small details that defy physics. And while this image is undoubtedly artificially produced, only a little prompt engineering can make it harder to distinguish from human art. Here’s a version where I asked ChatGPT to make the image more like a watercolor:

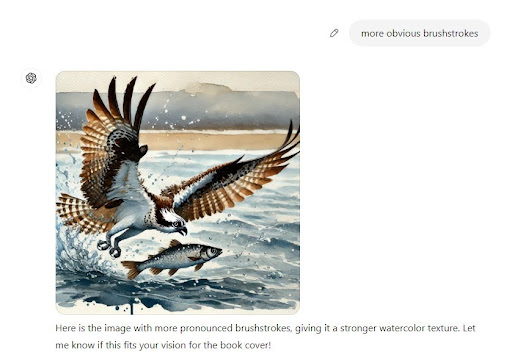

And a third (and final) draft where I asked for more pronounced brushstrokes…

Basically, genAI images are easy to identify when the prompt is vague, but harder to differentiate as it’s asked to draft increasingly specific versions. That same logic applies to large language models as well: general prompts produce more generic, obviously AI-created content, whereas repeated prompting and narrowing constraints can produce content that might pass as human-generated. Still, there are strategies for differentiating between AI-authored content and human-written text.

GenAI and creative writing

Like with images, writing produced by genAI skews toward being generalized. With creative writing, that means prose that favors summary and relies less on complex, multi-sentence exchanges of dialogue (for example). This can be a challenge for volunteer submission readers and editors of lit mags and small presses. After all, these aren’t pitfalls exclusive to genAI authors. Emerging writers might submit drafts to publishers that exhibit similar issues: an imbalance of summary writing versus action, shorter-than-needed conversations between characters, and more. How do you know the difference between an early-career author with a rough draft and a good idea, compared to a large language model doing an impression of them?

One answer is grammatical precision. Often, creative writing produced by genAI tends to be close to grammatically flawless. That’s especially true if the piece is short, and there are fewer opportunities for the LLM to stray off topic. Compare that to a human writer. Usually, emerging writers evolve steadily and incrementally, becoming a skilled prose stylist, plotter of action sequences, and capable grammarian in equal measure. It would be unnatural for a novelist to suddenly master complex sentence writing, while their ability to flesh out characters lags far behind. Comparing one off-the-charts skill to the other qualities of a submitted piece might help lit mags and publishers better identify genAI writing.

For the New York Times, novelist Curtin Sittenfeld pitted herself against ChatGPT. Both wrote a short story in the voice of Sittenfeld, and the results were included without bylines in the article. The longer each short story went on, the more apparent the differences became (between Sittenfeld’s work and ChatGPT’s output). Sittenfeld reaches the conclusion that ChatGPT’s language and emotions didn’t seem similar to her fiction. “In fact, and this might be the ultimate insult,” she writes, “ChatGPT’s story was so boring that I wouldn’t have finished reading it if I hadn’t agreed to this assignment.”

Again, ChatGPT isn’t the sole producer of boring stories, but these qualities– perfect grammar but thin substance, an egalitarian narrator who treats asides and essential plotlines equally, tinny dialogue (“What’s your favorite fruit that’s considered a vegetable and what’s your best episode of TV ever?”)– can help readers sniff out a genAI piece during their reviews.

Trust your critical eye

Most readers and publishers have read hundreds, if not thousands, of unique stories. You’ve cultivated a unique barometer for human-generated narratives, probably without even knowing it. Be sure to trust your instinct when something feels off in the submission you’re considering. Remember: LLMs are only trained on previously published content. By nature, they will almost exclusively produce stories that favor tried-and-true plot points, scenic details, and conversational topics. After all, you won’t find a unique story premise in a batch of training data– that wouldn’t make it unique!

Tools to weed out genAI

Apart from your own internal compass, tools exist to help readers identify genAI content. Grammarly, for example, touts its own genAI detection, which displays a percent score when evaluating how much of an input might be generated by AI.

Perhaps you’re worried about the irony of using one of the most genAI-reliant writing tools to detect genAI content. That’s okay—there are alternatives to Grammarly. Consider something like the subscription-based Originality.ai (geared toward publishing professionals and journalists) or ZeroGPT, which operates in a similar way. Users input text, and ZeroGPT’s system evaluates the writing on a spectrum from “your text is human written” to “your text is AI/GPT generated.”

These tools aren’t ironclad, but they can help you interrogate a first impression. If you are worried about whether a piece has been authored by a human, use a tool like ZeroGPT or Grammarly to test or challenge your knee-jerk reaction.

Wrap-up

Honing your ability to identify genAI underpins your desire to welcome its use or to oppose its growing reach. Hopefully our walkthrough—of genAI’s beginnings, current manifestations, and its hallmarks—will help you parse the written from the aggregated. From there, authors, readers, and publishers can begin to form, articulate, and share their own stances as they pertain to generative AI.

Kevin Breen lives in Olympia, Washington, where he works as an editor. He is the founder of Madrona Books, a small press committed to place-based narratives from the Pacific Northwest and beyond.