We spoke with the 2020 recipients of CLMP’s Golden Colophon Award for Paradigm Independent Publishing about the origins and future of their eleven-year-old press.

What is the history behind Dorothy, A Publishing Project? When was it founded and what was its original mission?

Danielle Dutton: Dorothy started in our tiny ugly kitchen in Urbana, Illinois, in 2009. We were both working at Dalkey Archive Press then, which was what brought us to central Illinois after grad school in Chicago and Denver. Marty was the associate director, and I was doing the book design and only working part-time at that point, largely from home, while taking care of our newborn. I’d wanted to start something for a while, and I think that feeling came to a head while I was pregnant. I just felt so out of things, post-grad school, pregnant in downstate Illinois. I wanted to make stuff and I wanted to talk to interesting people. So it was something we discussed a lot in our spare time, but I couldn’t see exactly what to do.

Danielle Dutton: Dorothy started in our tiny ugly kitchen in Urbana, Illinois, in 2009. We were both working at Dalkey Archive Press then, which was what brought us to central Illinois after grad school in Chicago and Denver. Marty was the associate director, and I was doing the book design and only working part-time at that point, largely from home, while taking care of our newborn. I’d wanted to start something for a while, and I think that feeling came to a head while I was pregnant. I just felt so out of things, post-grad school, pregnant in downstate Illinois. I wanted to make stuff and I wanted to talk to interesting people. So it was something we discussed a lot in our spare time, but I couldn’t see exactly what to do.

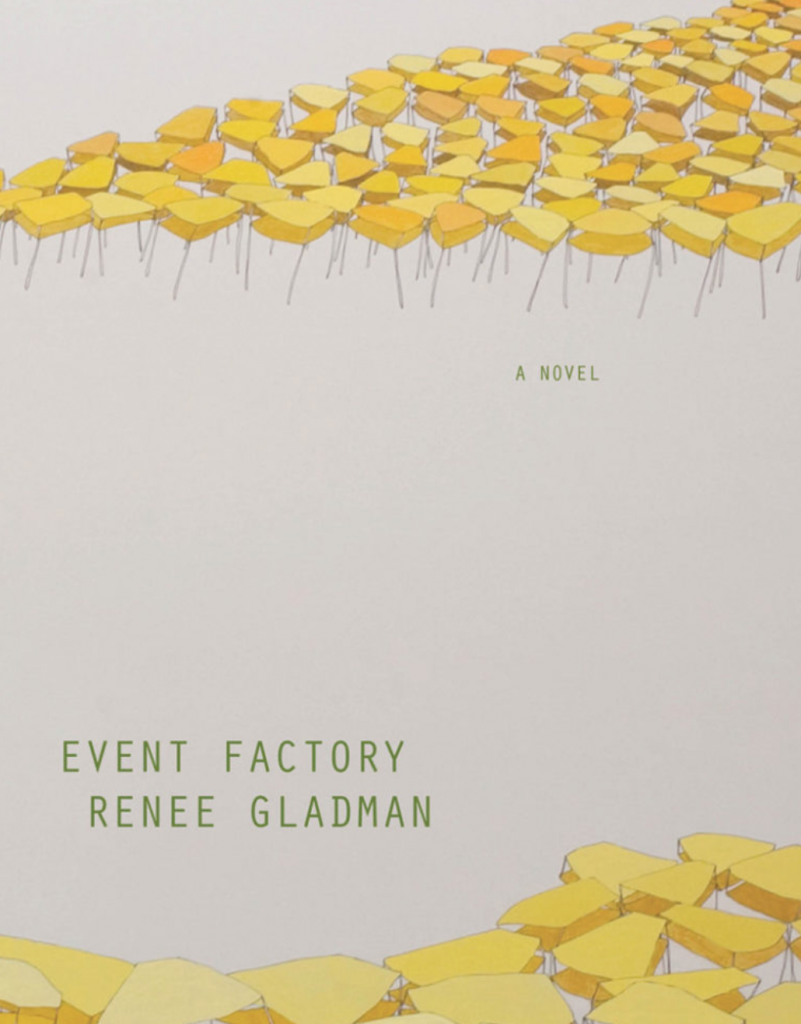

The catalyst for what ultimately became Dorothy was a rumor we heard that the writer Renee Gladman had a series of novels she was writing set in an invented city-state called Ravicka. We were both huge admirers of Renee’s earlier works of prose, and somehow when we heard about these books all our discussions started clicking into a place.

The mission was utopian. We wanted to create a space in the culture dedicated to celebrating smart, strange, difficult, innovative fiction by women. We had no idea if anyone would ever read the books, buy the books. It honestly felt a little like a private dream at first.

What inspired you to publish only books by women?

DD: It was complicated, based partly on stuff in the culture and partly on my own experience. To the second: at that point in my life, I just thought working with women would be more comfortable for me than working with men. I mean, this is all sort of private stuff, but I haven’t always had the best experiences with male colleagues or bosses throughout my life (from being ignored to being bullied or sexually harassed), and then the vast majority of people who have pushed back against my authority when I have been in a position of authority have been men. Basically, I wanted to collaborate with writers, to build relationships with them, and that seemed more like a thing I could productively imagine doing with other women. But there was also this aesthetic and cultural side to the decision, which was complicated in its own way: from seeing how few women submitted their work to Dalkey, to having heard a lot of misogynistic crap about female authors over the years, to wanting to create a space that seemed to be missing in the literary world, to the simple fact that most of my favorite writers are and always have been women.

At CLMP’s annual benefit where you were presented with the Golden Colophon Award for Paradigm Independent Publishing, Barbara Epler, president of New Directions Publishing, said of Dorothy’s books, “I love that they streak across the sky every autumn, the genius of just two books a year, just carried out perfectly.” How did you decide to publish two titles annually at the same time? What are some of the rewards and challenges of this model?

Martin Riker: That decision was both philosophical and practical. We’d assumed going in that we would lose money each year, and would make up the difference from our day-job salaries. When we drew up a budget, two books per year was what we figured we could publish with the amount of money we felt we could afford to lose. It also helped with the issue of time, which has always been in even shorter supply than money. We were going to be a small operation, no matter how you factor it, so what we would have to offer that bigger presses couldn’t or wouldn’t—we reasoned—was time and care. If we limited ourselves to two books per year, we could pour a great deal of energy into each book. Since we both had a lot of publishing expertise, that time and care would really be worth something. We didn’t want to pursue this project just to print a bunch of bound paper; we needed to feel we could offer something particular and valuable to each book.

Martin Riker: That decision was both philosophical and practical. We’d assumed going in that we would lose money each year, and would make up the difference from our day-job salaries. When we drew up a budget, two books per year was what we figured we could publish with the amount of money we felt we could afford to lose. It also helped with the issue of time, which has always been in even shorter supply than money. We were going to be a small operation, no matter how you factor it, so what we would have to offer that bigger presses couldn’t or wouldn’t—we reasoned—was time and care. If we limited ourselves to two books per year, we could pour a great deal of energy into each book. Since we both had a lot of publishing expertise, that time and care would really be worth something. We didn’t want to pursue this project just to print a bunch of bound paper; we needed to feel we could offer something particular and valuable to each book.

We actually started making money early on, so the budget reason went away. But we’ve valiantly fought against our own temptation to expand (whenever something goes well, it makes you feel like you ought to expand) because if we expanded, we’d still be small, with all the disadvantages that come with being small, but without the one big advantage (time, care) that has made Dorothy worthwhile in the first place.

The biggest problem with doing only two books was that the conventions of the publishing industry aren’t set up for that. We were very fortunate that Small Press Distribution was flexible enough to take us on. Still, you can’t do a catalog for two books, you can’t really set up a media meeting with a books editor, and so on. We decided our best chance was to proceed as unconventionally as possible, and from this came the idea of publishing the two books on the same day, in the hope that it would be a sort of “event.” Philosophically, Danielle wanted the books to represent a wide aesthetic range, to gesture toward the aesthetic breadth of fiction—and the fact that literature’s value lies largely in its aesthetic breadth, its multitude of voices—so pairing and publishing the books together made sense on that level as well.

What we did not anticipate was the level of enthusiasm and goodwill we would be met with, both from readers and from people inside the industry. For all the planning we put into trying to exist unconventionally within a conventional publishing structure, none of it would have turned out very well without that.

Phew! That was a long answer. But hopefully useful to someone out there thinking about launching their own project.

Epler also spoke about how beautiful your design is. Can you tell us a little about the process behind designing your books? And is there a story behind your owl logo?

DD: Yes, the owl logo comes from the fact that my Great Aunt Dorothy, whom the press is named for, used to send me books stamped with owl bookplates. Our owl was beautifully drawn for us by the artist Yelena Bryksenkova, who also did art for the covers of our editions of Barbara Comyns’s Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead and Manuela Draeger’s In the Time of the Blue Ball, translated by Brian Evenson.

DD: Yes, the owl logo comes from the fact that my Great Aunt Dorothy, whom the press is named for, used to send me books stamped with owl bookplates. Our owl was beautifully drawn for us by the artist Yelena Bryksenkova, who also did art for the covers of our editions of Barbara Comyns’s Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead and Manuela Draeger’s In the Time of the Blue Ball, translated by Brian Evenson.

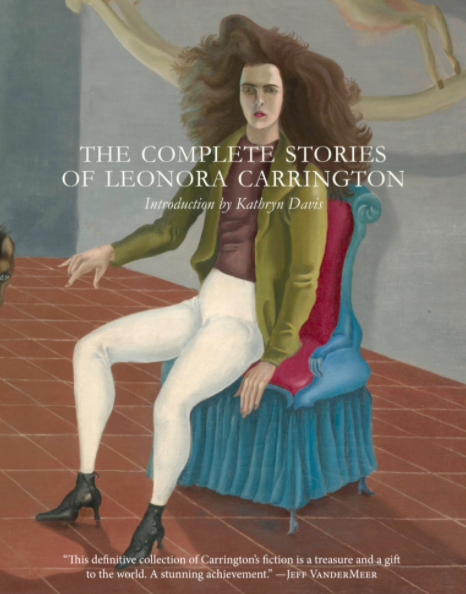

As for the book design, I do all of it, with input and helpful push-back from Marty. We didn’t set out with a particular design aesthetic, other than my own propensity for green, perhaps, and also the fact that I’m not a trained designer, which places very specific sorts of constraints on what I am able to do. I think from the beginning I just wanted to find cool art to feature on every cover, and that’s definitely one of my favorite things to do, that matching up of the feel of a writer’s aesthetic with a visual artist’s vibe.

Dorothy, A Publishing Project celebrated its tenth anniversary last year. Can you tell us about some of the 22 books you’ve published in the past 11 years?

MR: We’ve always been drawn to publishers whose lists have a personality. As new books are added, it’s not the list’s personality that changes, just your understanding of it. As if the publisher’s entire list already exists, and what happens each year is that you get to know more of it. We’ve always thought of Dorothy’s list like this, as being at once fluid and coherent. It also means that all of the list is equally present all the time. We of course treat new titles as “frontlist” for practical purposes (if only because the best way to give a book a solid long backlist life is to give it a solid long frontlist life), but at the end of the day, there’s no front- or backlist for us, in that sense. Practically, this means we keep all of the books in print, which is by far our largest annual expense. But conceptually it means that in addition to the stories each of these books are telling, there is a meta-story of Dorothy, and that story, the revelation of Dorothy’s “personality,” is enormously important to us.

In BOMB Magazine, Kate Zambreno referred to your work as “a list that has become its own canon, challenging and upending the potentialities of fiction in this current landscape.” Can you speak more to how you see the books you publish as relating to or conversing with one another and with the wider publishing landscape?

MR: I love that Kate’s quote recognizes that element of aesthetic coherence I mentioned above. If I would substitute the word “personality” for “canon,” it’s not because a personality is freer (a canon, too, can be a place of possibility), but because “canon” might place too much emphasis on how much “the current landscape” means to the decisions we make. Certainly, Dorothy’s origins came out of Danielle’s desire to address a lack in the culture, and that was a very formative factor in setting out. But an alternative canon is something built alternatively, while it would be very sad if a person existed primarily as an alternative to other people. We take on books because we love them individually, but our choices are also steered by this sense of the list as an entity, something that wants to conceptually expand. It’s this feeling that causes us to say, “You know, I think it’s time for another debut,” or, “I feel like we’re getting a little surrealism heavy,” or whatever pressures we put on ourselves to keep the list lively and interesting, for ourselves as much as for anyone else. Standing against can be a powerful strategy for social change, but so can simply existing apart, proposing a different, autonomous set of values.

MR: I love that Kate’s quote recognizes that element of aesthetic coherence I mentioned above. If I would substitute the word “personality” for “canon,” it’s not because a personality is freer (a canon, too, can be a place of possibility), but because “canon” might place too much emphasis on how much “the current landscape” means to the decisions we make. Certainly, Dorothy’s origins came out of Danielle’s desire to address a lack in the culture, and that was a very formative factor in setting out. But an alternative canon is something built alternatively, while it would be very sad if a person existed primarily as an alternative to other people. We take on books because we love them individually, but our choices are also steered by this sense of the list as an entity, something that wants to conceptually expand. It’s this feeling that causes us to say, “You know, I think it’s time for another debut,” or, “I feel like we’re getting a little surrealism heavy,” or whatever pressures we put on ourselves to keep the list lively and interesting, for ourselves as much as for anyone else. Standing against can be a powerful strategy for social change, but so can simply existing apart, proposing a different, autonomous set of values.

You are currently open for both agented and non-agented submissions through January 1. What are you looking for as you read submissions for books you’ll publish in the future?

DD: We’re always looking for something that feels and sounds different. It’s usually a good sign if I wish I’d written it myself. Beyond that, there’s nothing in particular, no subject, for example, that we’re hoping for or avoiding. It’s mostly to do with the energy and the music in the prose. Plus, as Marty was saying before, whatever we intuit the list needs, or needs to do.